Mossad operative G. has had many a heart-pounding moment as an intelligence officer and agent handler in enemy countries. The most emotional and scary moment, however, was on the last Independence Day at Mount Herzl in Jerusalem lighting a torch as a representative of the secret intelligence organization.

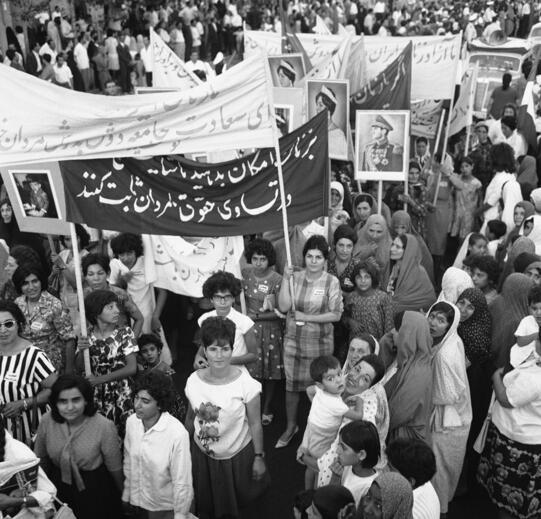

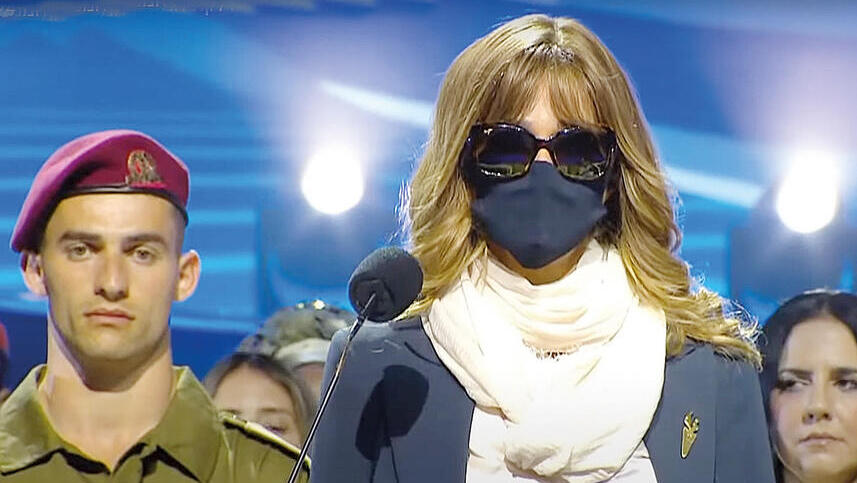

In the closed ceremony, filmed before broadcast, on a podium alongside 43 further representatives, she was faceless, ageless and with no identity. It simply said that she was born in Iran and that she had contributed to Israel’s security in the Iranian field.

9 View gallery

“I didn’t wear my own clothes,” she reveals. “I wore a scarf covering my neck, sunshades and a mask. I wore no jewelry that could be identified in any other situation. No Mossad representative has ever lit a torch before. I was in a whirlwind for two days leading up to the ceremony. I’m still overwhelmed.”

“I was home. The TV was on and I’d just made myself coffee. My husband was there. The children weren’t. Then, the Mossad chief called. I knew where it was going as before the final decision was made, my commanders had told me that – along with others – my name had been put forward. I was then notified that the Mossad chief had chosen me. He called me only after the committee had approved my selection. Being informed directly by him was very exciting.”

You must have known him before he became Mossad director.

“I had worked with him. He was head of Tzomet, the division responsible for locating, recruiting and handling foreign agents worldwide. I’ve been in Tzomet my whole life. I’ve had a lot of meetings and conversations with him. Sometimes he berated me, sometimes he complimented me. The Mossad director was an intelligence officer, as was his predecessor, Yossi Cohen. It’s a role that lets you reach your full potential.

“It’s important for me to say that I represent the Mossad, not myself, but rather everyone working for the Mossad. It’s not the Israel Defense Prize awarded to me personally. I’ve done things, very important things. That’s why I joined the Mossad. But on that podium, I wasn’t myself. For seven months, we’ve been seeing and hearing about amazing heroes all around us and lighting a torch is for great heroes. It was 48 hours before I could move or even talk about it.”

Did you tell your mother?

“My mother was so emotional she cried. She was a total puddle of tears. You have to understand who my mother is. She brought her children from Iran by the most perilous route. She’s the driving force behind everything I do and this was a kind of closure for her.”

And she can’t tell anyone.

“She knows the rules of the game. She goes with it. I told my friends in the Mossad and my inner circle of friends.”

Even sitting right in front of me, she wasn’t “herself”. She was wearing a wig and colored contact lenses, formal generic clothes and professional heavy make-up. She jokes that she was supposed to be better disguised with a full mask and false teeth like they do on TV for characters on Eretz Nehederet, often dubbed the Israeli Saturday Night Live, but that they let it go.

Ordinarily, she looks like a regular person, like anyone in the neighborhood. Our interview was conducted under strict field security restrictions. Even her voice was different. Two days later, however, she was stressing out.

9 View gallery

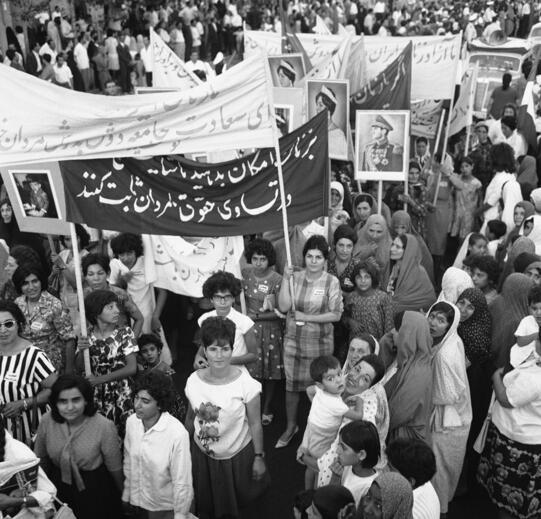

Iranian women protesting before the Islamic Revolution

(Photo: AP)

The woman who handles agents across the globe, flies around on secret missions and meets people who could kill her, was worried about the exposure. “I’m an active intelligent officer,” she says. “I’m involved, physically with my body and my voice – in ‘live’ operations.

We never underestimate our enemy and just as we have targets on their side, they have targets on our side. And what target is more attractive than a Mossad intelligence officer? That’s why not a lot of people know I’m a Mossad intelligence officer specializing in Iran, recruiting and handling agents in enemy countries.”

Unlike others, plucked young from dedicated intelligent frameworks into the Mossad, G joined the ranks of the Mossad when she was already married with children and had a career in another field. She was thinking of retraining in the field of education when she spotted a Mossad recruitment notice. I applied for a desk job and never thought of being an intelligence officer. I took the bait and was hooked,” she says with a smile.

Looking back at her life story, she seems to have been destined for this job. “I was born in Iran,” she says. “My childhood was fun – very much around the family. We had a rich community life. Iran looked and behaved like Europe at the time. It was more advanced and European than what was going on in Israel. Life was normal with friends and neighbors, mostly Muslim and Iranian.

Iranian society had a shared life with us, with shared experiences. We celebrated the Jewish holidays alongside traditional Iranian holidays – Iranian, not Islamic holidays. We celebrated Nowruz, Iranian New Year that falls around Passover with more or less the same customs – just without the chametz.”

The revolution changed everything for all Iranians. It was like going to sleep and waking up in a different world. It changed our lives completely, both as Jews and as Iranians. Our friends remained our friends even afterward, but all women from kindergarten age and up were suddenly required to wear head coverings.

Although the Islamic Republic’s platform is freedom of religion for all religions, Jews are prohibited from certain professions. Fewer Jews advance in the public sector for example. My parents’ lives changed a great deal, partly due to restrictions and partly to the atmosphere that had been created.”

9 View gallery

G. lighting a torch during Israel’s Indepedence Day

How did you get to Israel?

“There had always been Aliyah from Iran. Although the Jews lived in Iran as loyal citizens, the regime brands them as Zionists and assumes they’d get to Israel. So, Jews weren’t allowed to leave Iran as families. You’d always have to leave one family member there as ‘security’. My family chose to leave no one behind, so shortly after the revolution, we left a different way. I wish I could tell you how.”

“Integration in Israel,” she says, “wasn’t easy. There’s no mixed schooling in Iran. So, there I was, on my first day at a new school in Israel with student council elections in full swing. Music was blaring over speakers and boys and girls were all running around in shorts and t-shirts. Everyone was loud and cheerful. I was shocked. It took me time to take in that this is what school looked like. Having boys around was totally foreign to me.

“There was a stigma about Iran at the time. They would call us ‘Parsim’ (Persians) and mock our accents. I only had a tiny bit of that. Maybe I was in such a state of shock I didn’t notice. I was surrounded by school and friends.”

Did you remain Iranians at home?

“You don’t give up so easily on Persian food. My home has Persian music alongside world music. As I grow older, I go back to the Persian songs, stories and culture. Can you imagine? We couldn’t bring any property with us – just a little jewelry, but almost no possessions.”

As part of your job, have you gone back to the home you left behind?

“No. I don’t physically go to Iranian territory.”

Do you know who’s living in your home today?

“No. We don’t utilize Mossad’s amazing capabilities for personal use. If a person of interest to us were living there, we’d know. I have a great love for Iran and I make a clear distinction between the Iranian people and Iran – the regime occupying Iran for the past 45 years. But my home is here and my heart never leaves the home we left behind. I’d like to visit Iran for the children to see where I was raised, but I wouldn’t go back to live there. We always looked to Israel, even when things were good for us in Iran.”

Did you have childhood friends in Iran?

“Most of them have left too. I’ve met up with some of them.”

At class reunions, people always tell each other where they’ve gotten to in life. What do you say about your life?

“There’s the close family circle that knows, and then there are the broader circles. I don’t make up stories about being a doctor or a mountain climber. There’s a set cover story. In my private life, I’m very extroverted. I love people and draw energy from them. And then, there’s the world I can’t talk about, about which I can’t answer personal questions. You don’t always talk about that world. I also have my family, my children and life experiences. Alongside my work in Mossad, I have a regular life. “

So, let’s talk about the family and the children. Are you an active mother?

“Definitely. A Mossad intelligence officer isn’t the most regular job. It’s the most amazing and imaginative job there is. I have a very exciting life, but I’m also in the class WhatsApp group and I attend parents’ meetings and am even rather opinionated in these meetings. Yes, if I have the choice of baking a cake or bringing plastic plates to class events, I’ll bring the plates.

9 View gallery

Iranian missiles intercepted near Israel

(Photo: Atef Safadi)

“Like for any woman with a career, there’s a balance, and Mossad allows for that. Family, stability and the support you get from your partner are very important and I take off my hat to my husband. I won’t be at all the kids’ parties, but if there’s an event, it’s important I attend, they’ll move things around – not an entire operation, but leading up to the operation there are things over which we have more control that can be moved around.”

When the children are asked at school what their mother does, what do they say?

“Something along the lines of my cover story.”

It’s important for G. to explain that she’s not a Mossad agent, as people like to generalize. “We’re Mossad operatives. Agents are partners to our work. They’re on the other side, our fates are sealed together, and I recruit and handle them.”

How do you spot someone that’s right?

“It’s not up to me. I don’t go looking at the guy at the grocery store wondering if he’d be a great agent. There’s a whole mechanism that builds the intelligence picture and marks where the gaps are, what’s missing and where. They mark individuals who could fill those gaps and turn them into recruitment targets. We receive intelligence about them and get to work.

“Our agents do work that’s important for the security of the State of Israel. So, most of the population in enemy countries is not relevant for us. I don’t choose who would be convenient to recruit or who loves Israel. I get information about individuals and I have to adapt myself and it may be easy or difficult to recruit them.”

“Not should. Must. We’re done with the street. We’re already there. We’re aiming at much more significant places affecting the threat and that pose a threat to the country’s security. Everything we do is in line with Mossad’s goals of thwarting any kind of threat to the security of the State of Israel from all the enemies surrounding us. It’s big and includes the threat from Iran, the missiles landing on us a month ago and decision-making mechanisms. This is what interests us. That’s where we’ll aim and that’s where we’ll shoot.

“It means learning everything we can about the target, finding the right way to approach them. I don’t call them us and say ‘Hi, this is G. from Mossad. Let’s meet up.’ You need to find the right way to approach them, that will also protect them and make sure they’re not afraid to come meet us. I don’t meet them in Israel, and not as an Israeli. We get to know them gradually, build up trust, build a relationship. We peel off layers learning their dreams, threats and driving forces.”

9 View gallery

G. also stresses that she’s not alone. “The intelligence officer is at the front and it may look like they’re working alone, but they’re surrounded by a whole mechanism of tech, intelligence and HQ personnel – from the time I receive the file about the target right through to the stage of the fantastic operations we carry out.”

And how does it work in practice?

“Each person has their own operations mechanism. It’s not a metamorphosis a person has to go through. HUMINT (human intelligence) refers to a motivational force driven by deep personal connection and common ground. We have a lot in common with lots of our targets. They know they’re working for me and do what they do because of this deep personal connection.

“Part of the intelligence officer’s heart is invested in every operation and every target. It’s not mechanical. It’s a deep connection with a lot of truth to it. Much of what the agent does is due to this connection that’s been formed. We study this for a year at the intelligence officers’ school.

“My targets are people from within the mechanism itself, part of it. This is their livelihood. They also don’t really understand the true significance of the hostility between the two countries. They’re curious about us. They want to investigate and find out. The Republic of Iran is a common enemy. They do these things for their children’s future, for the future of a country open to the world. Eighty percent of those within the mechanism don’t believe in ideology. They have nothing to do with it.”

Do you have conversations with the targets, seemingly creating intimacy? To what extent do they really know you?

“I do a lot of intelligence officer training and I always tell them: A cover story may vary from one situation to another. The operation has stages to it. When a deep connection is being formed, you do bring yourself in. It makes no difference if I’m a mother of three, four, five or just one child. Motherhood is the most important part of the conversation. It makes no difference that I’ve been hurt or had my heart broken by someone dear to me. What matters, is the experience I share. So, yes, it’s sometimes tailor-made and always controlled. I’m not here to connect with people, but when I’m there, I bring part of myself.”

Can you tell us about a particularly complex operation?

“I had formed a connection with a certain person in a particular Iranian position in a field of special interest to us. His beliefs were religious, but mystical. He believed in divine protection and every decision needed the ‘Yes’ from this divine protection being. In every operation, there are junctions the target has to get past and needs to make decisions.

“The target usually has an emotional or rational conversation with himself or will consult someone close to them. This person would only consult with the divine protection and it was difficult to deal with. He was a hard nut to crack. You think you’ve seen it all, then you find yourself in a mystical world. I did crack it, but it took an extremely long time.”

As time passes, do some people become irrelevant?

“Our operations aren’t a microwave where you heat it up for seven minutes. These are operations that take lots of time and sometimes the same target is made redundant, or another intelligence officer is quicker than me and recruits another target from the same field, making the person I had been trying to recruit no longer relevant.”

What do you do?

“It’s heartbreaking. We don’t disappear instantly. We disappear slowly, very slowly indeed. There are no sudden moves in our profession. It’s all very slow and measured,” she tells us.

“A certain agent was involved in another operation. I knew he was there during the course of an operation, and I was so nervous about it. It’s an amazing, very special person and we had formed a deep bond. I was very worried about him as I knew what he was doing. I was at home with my husband and children and I couldn’t breathe.

9 View gallery

“At some point, I said to the kids, ‘I have a very dear friend doing something very important, and I want to pray for his well-being and safety. My sweet children did a kids’ prayer. They didn’t even know his name. They just called him ‘Mommy’s friend’. I’m crying as I tell this story. They prayed and everything was okay.”

You love the agents, and yet you send them into great danger.

“Let’s not get carried away,” she jokes. “I don’t love all of them. I love some, not all. But yes, they are in danger and an important part of an intelligence officer’s role is protecting the agents’ safety at all levels and in so many ways – from my first call, through long years of handling, including round-trip missions, we ensure our own safety and it’s successful.”

Have you ever moved someone to another place?

“Yes.”

Have you ever met your agents as you really are?

“No.”

Have you ever passed one of them on the street and they didn’t know it was you?

“Yes, but not in Israel.”

Has it crossed your mind that he’s lying to you like you’re lying to him?

“We take this into account when we make decisions. We have ways of finding out the truth and we have ways of making them come to the truth. If it’s the right thing to do, I sometimes tell them they’re lying. That’s one method. There’s always the fear of losing them, so I’ll only do that when they’re in a position they’re not going anywhere. Either that, or I’ll be able to bring them back.

“Like anything you’re invested in, you want it to work and you paint an optimistic picture in your mind. With time, you learn to have your doubts. You have a whole mechanism around you, which is cleaner and uninvolved, that helps create doubt. The role of my many commanders over the years has been to pose question marks. It’s part of the work, even over long-term handling. There’s never a stage where we rest on our laurels and shut our eyes. Our finger’s always on the pulse.”

Have you recruited women?

“That’s my dream. Very few. It’s much more interesting and a greater challenge. It’s just that there are fewer women in the kind of key positions we want. I have handled, but not recruited, women. I find the recruitment process a greater challenge. Handling has its own challenges.”

9 View gallery

Give me a handling challenge.

“We worked for a very long time on a big operation with lots of participants, agents, tech and intelligence personnel and intelligence officers who’d undergone extensive training – yet another fantastic Mossad operation. We were at the stage we were ready, with the agent in full gear just waiting for the operation.

“Very close to the green light, more information came in that made us think the operation’s timing may endanger the operation or its agents. We needed to rethink the matter in greater depth. The challenge was keeping my agent on hold for a prolonged period, by which time he already had a picture in his mind of what he was going to do. He had a key role and had been dreaming of it and training for it for months. ‘Just let me do it.’

“I wasn’t there the moment they needed to stop his departure on the mission and he refused to accept the ‘abort’ instruction from anyone else. We made contact with him and I spoke to him for a very difficult hour-and-a-half. I used everything I knew about him, all the things we had in common, all the bonding over time to make him do what I wanted.

“In the end, the mission was accomplished wonderfully, but this was an operational challenge both in terms of complexity and time invested. The recruitment process was different, with hurdles before the guy would go with the flow and do what I wanted.”

Does being a woman present problems recruiting in countries where women wear veils and have fewer rights?

“The most forceful characters in the life of any Iranian man are his wife and mother, so my being a woman is a non-issue. As a rule, I think being a female intelligence officer is even advantage. Not in a seductive way, but rather because women are generally less threatening and form bonds in a softer, more rounded and sophisticated way. There are female characteristics I believe are an advantage in this profession.”

Do you think that amid the conflict with Israel, Iranian intelligence officers are now operating to recruit Israeli targets?

“No way. I may well have an Iranian counterpart. But her chances of telling you 1% of what I’m telling you about Iranian achievements against the Zionist enemy are slim. I’m not underestimating my opponent. Quite the reverse.”

On the morning of October 7, she was in her home in Israel and, like everyone in Israel, heard about the horrors going on. “I didn’t immediately go to work,” she tells us. “Our work is before the war begins. Once the war has started, we don’t put on bullet-proof vests and get into the battlefield. Our response is different.”

As an intelligence officer, how do you see what happened that day and the intelligence and consequent exposure of security failure?

“What I feel as an intelligence officer and as an Israeli citizen has changed. The first month was horrific. Like any citizen, it took me time to process it all. I’ve always felt the responsibility weighing on the security organizations and on myself as a Mossad intelligence officer. It weighs heavier now. After what we went through, our responsibility at the Mossad against the arenas for which we are directly responsible, has become even clearer. A lot of hard work lies ahead.”

Does it hurt witnessing the extent of the failure?

“My heart hurts because my heart hurts. How is this related to my being an intelligence officer?

9 View gallery

Because you’re a human intelligence handler, as there were in Gaza.

“We receive lots of dangerous intelligence that sometimes doesn’t always line up with what we were thinking. Even before October 7, we didn’t ignore such intelligence and now, even more so, we won’t let ourselves ignore it, even if it doesn’t fit lots of indications. Building an intelligence picture is complex and hard work and you don’t base a situation overview on one indication. In the first month following October 7, I was sure we’d missed something. It couldn’t be that we had no indications.”

What did you do? Get back to work, re-examining files and recordings from sources?

“Not to the degree of checking recordings, but rather ongoing and in-depth conversations with various individuals who also wanted to look into the matter, not just me. In the end, I checked to see if there was anything I’d missed, but no.”

What have you heard from the agents you handle about the war Israel’s conducting?

“Depends from whom. From those who’ve been with us for a long time, and we know who they work with, we’re getting reactions of shock and regret, expressing confidence in our ‘give as you good as you get’ capabilities.”

Have you reevaluated the approach to Iran since October 7?

“We do that all the time. Both before and after.”

Can nonetheless we expect an ‘October 7’ from Iran?

“We’ve been invested in thwarting the threat from Iran for years. We’ve conducted operations against the Iranian regime’s ongoing efforts to build an atomic bomb. Some operations have been exposed but most haven’t. You can’t argue with the fact that at this stage, Iran does not possess weapons of mass destruction.

“You’re asking me if Israel will be surprised and wake up one morning with Iran having the nuclear bomb? I want to believe not. Our people are on it 24/7. I have faith that Mossad will carry on doing what needs to be done so that Iran doesn’t get the bomb. Our job is never taking our foot off the gas and never shutting our eyes.”

On the night Iran launched hundreds of missiles at Israel, G.’s feeling was completely different – one of satisfaction. “There are hundreds of people, including myself who had worked hard for many years to thwart the threat from Iran that night. I won’t say I wasn’t charged up when I went to sleep. My parents had gone to sleep. The children were sleeping and my husband was snoozing, but I was sitting in front of the TV, safe and certain. I wasn’t smiling to myself. I don’t generally smile to myself when I watch the news, not even inside.”

Do you ever feel like showing off?

“Within the organization, we show off to each other. We have events and conferences where intelligence officers sit around and each one wants people to display their name, recruitments and the commanders who think they’re great. There’s very healthy competition between us. It’s the big league with the broadest spectrum of very talented people you could ever imagine with entire worlds of content you’d never believe. We show off within and we don’t need to show off outside.

What does your husband say about this double life with calls at all hours?

“My husband’s a real legend. He’s my anchor, the wind in my sails. He understood what it was all about as I was training, and then in real life too. It’s not a bed of roses. There’s stuff you need to deal with, but even though he also has a demanding career of his own, he’s totally in.”

“Do you know how proud he is of me? We have greater goals than me, him and everything. It’s perfectly clear to us why I do this, why I’m away from home, why we pay the price. Because I’m now all in, I don’t feel I’m paying a price. I’ve gotten so much out of it.”

“In my family, I also don’t feel I’ve paid a price or sacrificed anything. Yes, there are moments in family life when I’m not there. I wasn’t there for my daughter’s first kiss and although it might sound like nothing, she only told me the next day and it upset me. But when I think about it now, I just think ‘so what?’ and so does she. I even laugh about it.”

9 View gallery

From ‘Tehran’

(Photo: PR)

Did you watch the TV series, Tehran?

“Yes, but what we do is way past what you see in the show. My job isn’t what Sultan does. It’s much more.”

Like James Bond?

“It’s just fun. I’d be glad to have his gadgets live in hotels and wear fancy suits, but that’s not what our lives are like. I can be walking around beautiful places for a week in the nicest suits and the glitteriest story, and then I get home with laundry waiting for me and the Shabbat cooking needs to get done and all the things the children have to tell me, along with chores I left my husband that he hasn’t done.”

“It’s important for your readers to realize I’m not Wonder Woman with wings sitting here, but a woman with all kinds of capabilities alongside being a regular person leading a regular life. I’m a wife, mother, friend and daughter as well as a very proud intelligence officer and all these things can exist simultaneously. It’s not an either-or thing.”

Now tell me, your daughter comes home from school, gets on your nerves and you tell her off. Voices are raised, and then you need to, very calmly, talk to an agent. What happens?

“Why don’t you ask me what happens after talking to an agent about something very specific, I handle a crisis, deal with who I have to deal with, hang up and call the next agent where I’m someone else with a different story, managing a different situation? Transitions are part of our lives. So, intelligence officers are very flexible people. A moment before each conversation, I remind myself who I am. I’m G.”

Do you ever come home from an amazing operation to people bothering you with nonsense?

“Definitely. I come home to millions of messages and say to myself ‘Really? Look where I am and look where they are’. Is this what I came down from Mt. Olympus for? Over the years, I’ve realized that at the end of the day we, in the Mossad, do what we do so that your daughter can complain about school, and to allow the everyday for everyone.”

What are your plans for the future? Maybe Mossad Chief?

“I want to be Israel’s ambassador to Iran. We’re working on it.”